In February 1988, I sat in a plain interrogation room in Portsmouth, England, under arrest. I had been warned that what I said may be used to prosecute me, and my answers were written down word-for-word by a naval policeman, then taken page-by-page to be typed up for me to sign. I was asked detailed questions about my sex life and about whom I counted among my friends in the armed forces.

I was 22 and just beginning a career as a British Royal Navy officer, but I found myself at the centre of an intensive and determined investigation that resulted in the loss of my job, my forced outing as gay to family and friends, and the loss of my home and my place in university. My whole life was being uprooted. Within just a few days of the interrogation, I sought refuge inside a roll of old, discarded office carpet in a quiet street in London’s West End, too scared to go home to my family, where I would have to explain what had happened.

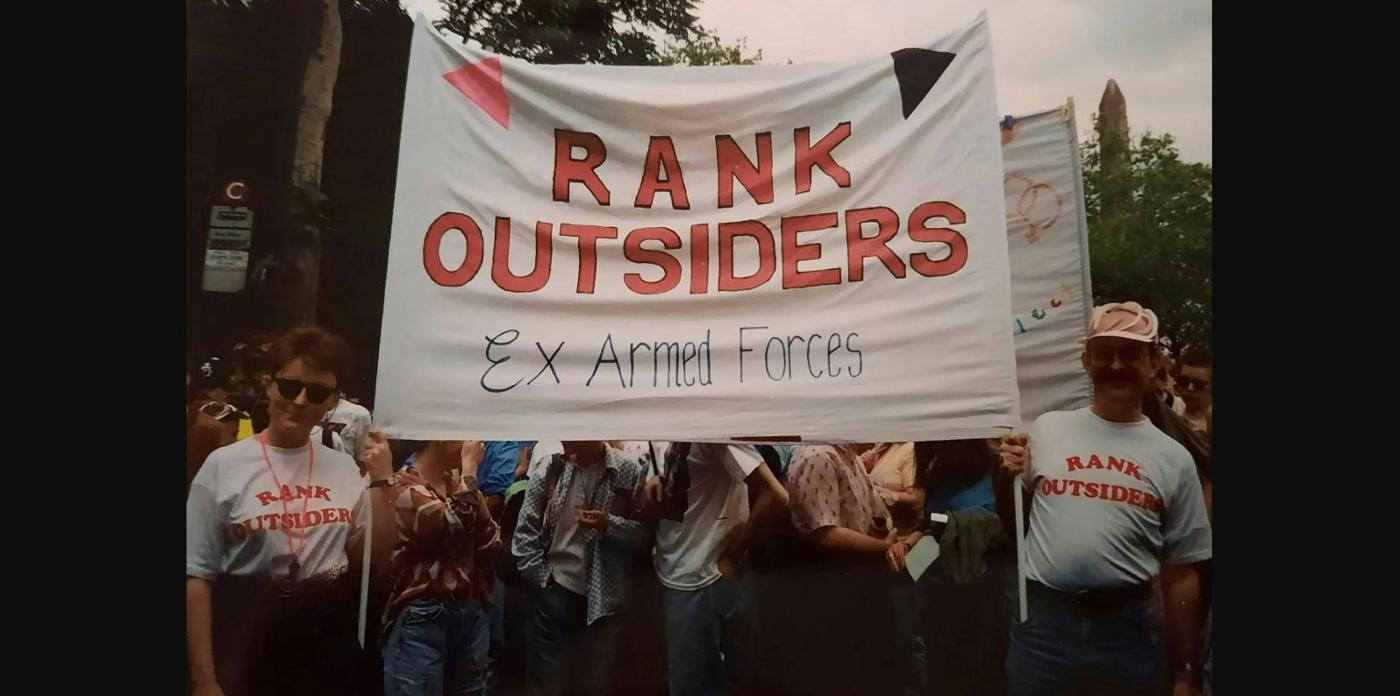

Despite all of this, you’ll be surprised to learn that mine was a relatively pain-free outing and exit from the armed forces. In the years that followed, I met dozens of other men and women who had been through much worse than I had. I met former service men who had been to prison, simply for being gay, even as late as the 1990s. I met women whose diaries and letters were seized by military police officers, sparking lesbian investigations that literally spanned the world, from Germany to Hong Kong. Motivated by these injustices, I found myself at the heart of an organisation, which was set up to provide support for people like me. It was called Rank Outsiders. I first met the group at a Gay Pride march in London, and quickly got involved, helping them to operate a weekly helpline for people experiencing situations similar to ours.

Although homosexuality was partially decriminalised decades earlier, it remained illegal to be gay in the armed forces until 2000.

© Sky / The Pink News

Rank Outsiders was led by Elaine Chambers, a former army nursing officer who had been dismissed, and Robert Ely, a former army bandmaster who had also been fired from service. Elaine and Robert were two remarkable people who had channelled their terrible experiences to create a safe space where dismissed service people could meet and find understanding amongst others who had faced similar horrors. Where else could a man find an outlet to admit that he had been forced by military prison guards to clean a toilet with his toothbrush, and then use that toothbrush to clean his teeth, as had happened to Mike, a young Royal Air Force airman, who went to prison after admitting to being gay in 1994?

Mike still feels daily the calculated pain and humiliation that he suffered, and finds it incredibly hard to discuss. His life was shattered as a direct consequence of a policy excluding all lesbians and gay men (even those who were celibate) from the British Armed Forces. In its absolute policy of exclusion, even in cases of abstinence, the British Armed Forces were even more discriminatory than the Catholic or Anglican churches at the time. The government argued that even the presence of a celibate lesbian or gay man in the military would be injurious to good order and discipline. Government ministers said on many occasions in interviews and in parliament, that the presence of homosexuals would have a negative impact on fighting efficiency.

Former army nurse Elaine Chambers was forced to resign from the British Armed Forces in the 1980s for being a lesbian.

© Sky / The Pink News

From active service to activist

Over the years following my dismissal, I became politically active rather than just angry. I found the focus and energy to start the Armed Forces Legal Challenge Group. By that stage in my life, more than five years after being dismissed, I had found a new career in journalism, and those new skills helped me to become an effective and recognisable voice for the campaign we began. A year later, in 1995, we had assembled a group of lawyers, lobbyists, and had found the four test cases that made their way to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, finally succeeding in their aim to override the ban against LGBT+ people in service in 1999. In January 2000, the British law was reformed, and in the succeeding two decades, the environment for lesbian and gay British service people has changed beyond all recognition. Today, there are out gay people serving in all branches of the UK military, some of whom are entirely unaware of the ban against their identity that preceded their service.

In a quite staggering example of the passage of time, I have now met members of the British Armed Forces who have reached the end of their service, and who are leaving the forces after a full career served entirely after the ban was lifted. It’s easy then to imagine that everything I’m writing about is an interesting, albeit sad, piece of military social history: a perspective that is of the past, of interest to academics and historians, but not of direct relevance to members of the armed forces today. But that is not the case.

Some NATO Allies are better LGBT+ allies than others

During my time as a campaigner for LGBT+ rights in the armed forces in the 1990s, I wrote a book called, We Can’t Even March Straight that became something of a catalyst for the movement that followed. It was recommended as essential summer reading by the Economist, which indicates perhaps how high profile the issue had become by that point. In researching the book, I visited a wide range of NATO countries and spoke to representatives of their armed forces about their laws and rules, and their knowledge of and policies towards lesbian and gay service people. What I found was that many NATO countries had never had exclusionary policies. Some chose to effectively enforce bans via ‘good order and conduct’ type catch-all provisions, and some had actively chosen to accept lesbian and gay colleagues into their forces. I met, for example, openly gay Dutch marines who had served in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Australian Air Force and Army sergeants with distinction who were serving openly, including within the recent theatres of conflict in the Gulf. Those findings contrasted greatly to the concurrent dismissal by the Royal Air Force of Sergeant Simon Ingram, the proud recipient of a Gulf War Medal for his service as an air electronics specialist during the conflict.

In many ways, I held up other NATO Allies as examples for UK policy-makers of best, or at least better practice, when it came to the management of this issue. In an interview with the Ministry of Defence in 1994, a British Army spokesman told me, perhaps partly in jest, that the Dutch Armed Forces were a bad example as they had trade unions and didn’t work at the weekends. I interviewed a sergeant from the Royal Australian Air Force who had even served on exchange in the United Kingdom, openly, and without problems, wholly supported by his own defence organisation. By the use of comparison, I was able to make the United Kingdom’s position appear antiquated and out-of-touch with the modern world, and with more liberal allies.

It is very interesting so many years later to see how dramatically the world has been turned on its head. The British Armed Forces, alongside their counterparts in many NATO countries, now embrace and celebrate its diverse workforce, while many Allies that were quietly accepting - but not welcoming – of LGBT+ service people have largely remained in the same place they were 30 years ago. In the armed forces of these countries, being gay isn’t a formal legal impediment to service, but you’re encouraged to keep it to yourself. These changes put me in the strange position of having to shift my ground from being a vocal and prominent critic of policy in the British Armed Forces, to being something of an advocate or ambassador for the remarkable way in which the service chiefs have embraced what must once have seemed like a very odd Brave New World.

A sea of change in opinion

I recently spoke at a panel on this subject alongside Admiral Sir Alan West, a former First Sea Lord (the highest-ranking officer on active duty in the Royal Navy), Head of the Navy and four-star admiral, and discovered how much impact he had quietly had in bringing the ban against LGBT+ service people to an end. For a man long since dismissed from the forces for being gay to find himself alongside one of the UK’s most impressive post-war military leaders was daunting, and would have been unthinkable 25 years ago. He apologised to me and to all lesbian and gay people forced out of the British Armed Forces, as in recent years have our armed forces ministers, our Secretary of State for Defence, and even, last July, our Prime Minister.

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Rishi Sunak makes a formal apology to LGBT veterans in the House of Commons on behalf of the government, 19 July 2023. © Andy Bailey / Parliament via Reuters

Members of the British Armed Forces now march at Pride parades around the UK in uniform. Military bands have also taken part, to the cheers and roars of the crowd’s almost universal approval. As armed forces around the world seek to attract young candidates with more liberal and open minds than many amongst previous generations, the positioning of the armed forces as a beacon of progressive modern values is a vital recruitment tool. Of course, in many countries, there remain critics of the flying of rainbow flags at army bases, but the truth is that the armed forces are not seeking to recruit thousands of bigoted and angry people: they need service people who believe that the armed forces are not just defending modern democracies, but are part of them.

While the enemies of democracy are banning Pride parades, enslaving women, and hurling gay men to their deaths from the roofs of buildings, it’s not really hard to see why lesbian and gay people would want to serve their countries. And we can see from the distinguished records of many, that they are among the most capable and committed of service members.

In recent years I have watched the UK, formerly one of the most actively anti-LGBT+ militaries in the Alliance, move to become one of the most accepting, and proving that armed forces are not more efficient when they are homophobic, misogynistic or racist. Young people have to make choices about their future careers, and the armed forces need to demonstrate clearly and visibly that they are a good and moral choice for those young people. In my view, a few rainbow flags – with resolve behind them - go a surprisingly long way towards achieving that.

Demonstrating allyship with formerly marginalised groups is a vital way of proving that a decision to join the armed forces is not a request to enter a time machine and go back to the 1950s.

More inclusive militaries are stronger militaries

The role of defending our democracies has rarely been as important as it is now, certainly not before in my lifetime. If we are going to maintain a military alliance that has the widest possible support of the societies it seeks to defend, that alliance needs to embrace and celebrate the extraordinary diversity of the communities it represents. There are LGBT+ people serving in many of our armed forces today, and celebrating their inclusion makes our Alliance stronger, not weaker.

25 years after I was fired, I sat in the audience at a human rights awards ceremony with friends: it was a grand party with champagne and platters of lavish canapes. Imagine my surprise when an award for the best LGBT+ employer was won by the Royal Navy and accepted on stage by an admiral. To the embarrassment of my friends, I immediately burst into tears. It was probably the first time I realised that I didn’t now need – nor had I ever needed - to feel shame and embarrassment about what had happened to me.

It takes active and visible steps for military leadership to demonstrate that they represent a modern and caring employer, and if stepping out of their important panelled offices in their uniforms and marching alongside a group of flag-waving LGBT+ service people can have the effect it’s had in the UK and some other NATO countries, I thoroughly recommend it.