A notable feature of East-West relations during the past year is the extent to which they have been marked by contradiction. The high promise of the Final Act of Helsinki has been followed by the grave events in Angola. The significance of moves towards a relaxation of tensions in Europe has been put in question by the steady expansion of the military strength of the Warsaw Pact. Hope for the freer movement of peoples and ideas has been weakened by recent notable examples of continuing severe restrictions. Signals have been alternating between red, green and amber, sometimes with all three flashing at the same time.

It is no wonder that Western public opinion appears to view the present state of East-West relations with some uncertainty, and even bewilderment. And this perplexity is nowhere more apparent than in the confusion over the whole concept of detente. What is detente? What is the meaning of this mysterious French word which has no equivalent in either the English or, more significantly, the Russian language?

In the recent past, some Western commentators have tended to interpret detente as implying friendship, an end to confrontation and a beginning to an era of cooperation. This optimistic interpretation is less frequently heard nowadays. Certainly, Western opinion is virtually unanimous in demanding that detente should eventually lead to a fully normal and natural relationship. But it is now widely recognised that this is a long-term goal, and that for the purpose of our strategy and objectives in the foreseeable future we are dealing with a very different sort of phenomenon. Indeed, so wide has become the variety of interpretation of detente that some Western statesmen have recently said that they do not intend to use the word any more.

Much of the confusion surrounding detente in the West might have been avoided if we had taken more notice of what the Soviet leadership had said about it. They are quite frank in defining the parameters within which detente is to operate. In Soviet thinking, detente is synonymous with peaceful co-existence. Its basic purpose is to provide a means of governing the relationship between the Soviet Union and the West, in order to avoid direct military confrontation, and in particular to avoid a nuclear war.

On the other hand, detente was never intended by the Russians to create a stable world order on the basis of the status quo. The Soviet leadership have gone out of their way to emphasise that the Helsinki Final Act does not mean an end to the East-West ideological conflict. Indeed, in their eyes detente creates greater opportunities for pursuing that struggle. We are at present seeing in Africa just what this can mean in practice.

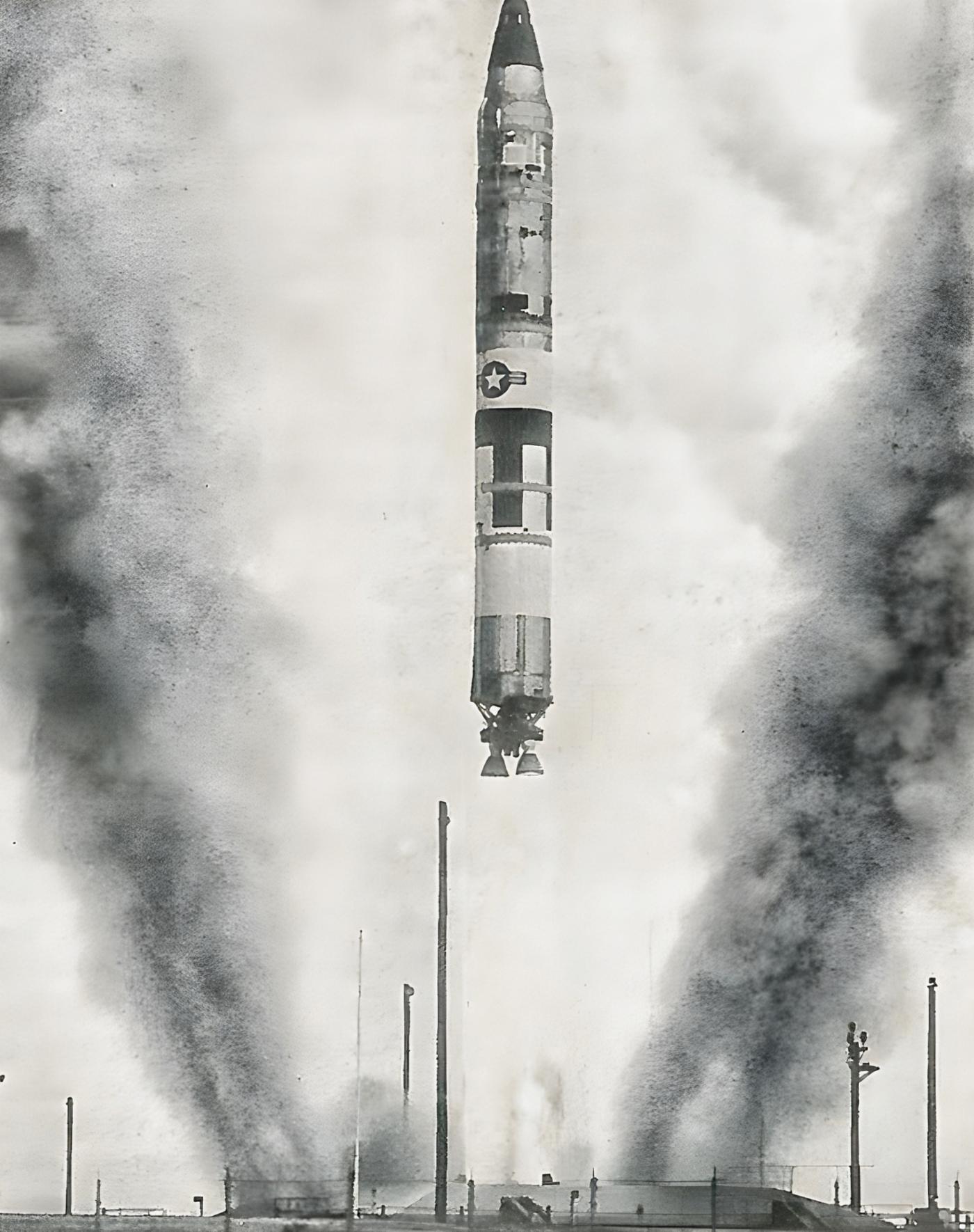

It is important to realise what has happened in Angola. While professing their dedication to detente, the Soviet Union and Cuba supplied a massive amount of modern arms and troops to support a rival political movement which was fighting for control of a newly independent state far beyond the limits of major Soviet national interests or of established Soviet influence. This is a blatant use of military might to expand the Soviet sphere of influence, and is a most serious development.

One remarkable feature of Soviet intervention in Angola is that their massive arms lift has been operating at the end of an 8,000 mile line of communication. This achievement illustrates the great growth in Soviet military strength on a worldwide basis.

Soviet T-72 battle tanks, seen for the first time in public last summer, as they rumble across Red Square

This brings me to another major limitation placed by the Soviet Union on the scope of detente. The Soviet Union has never seen any inconsistency between their conception of detente and the steady expansion of their own military strength. They have no difficulty in reconciling the policy of peaceful co-existence with an increase in their armed forces to levels beyond their defensive needs. And there is no doubt that there has been a continuous improvement in the quality and quantity of the weaponry, equipment and training of Warsaw Pact forces, as well as a growing emphasis on offensive operations.

This then is the Soviet view of detente: a reasonably stable relationship with the West at intergovernmental level; but the continuation of active ideological struggle, including support for any group they choose to call a liberation movement; and the persistent growth of Soviet military strength. In the face of such policies what should be the strategies and tactics of the West?

Strategies for the West

In these circumstances a realistic policy would seem to call for a double-pronged approach. First, it requires sufficient military capacity on the part of the West to prevent Soviet expansionism. Secondly, it requires policies designed eventually to encourage a more natural and normal relationship. And in their turn, both policies depend for their success on firm support from governments and public alike for a vigilant posture over a long period of time.

The first requirement means that the Alliance should clearly be seen to be in a position to fulfil its prime responsibility to deter potential aggression, and, should aggression occur, to repel the attacker from the territory of any ally. The deterrent capacity of the Alliance is the foundation for the security of every member. Were we to allow its credibility to be undermined we would be guilty of provocation of the most serious kind – the sort of provocation which tempts an ideological opponent to judge that aggression will pay.

Not that this aggression need necessarily take an openly military form. The danger is at least as much one of political pressure. We know that the present Soviet leadership attach great value to military strength as a means of applying Soviet political pressure both in Europe and elsewhere. Future Soviet leaders might be even more active in seeking to exploit this source of political influence.

In order to respond effectively to this challenge a real and continuing effort is needed from the Alliance. We have to be willing to devote sufficient resources to maintain the credibility of the deterrent shield. Some time ago it was comparatively easy. We could rely on the strategic nuclear superiority of the United States. But those days of superiority have gone and are unlikely ever to return. We are now in an age of approximate nuclear parity. This means that conventional forces are once more of the utmost importance. NATO's policy of flexible response depends on the "Triad", and within that Triad on adequate conventional forces as well as strategic and tactical nuclear forces. If our conventional forces become weak, Western leaders could be faced with the alternative of either bowing before a military fait accompli or before political pressure, or resorting to a nuclear response. The Soviet Union, for its part, is steadily increasing its conventional as well as its nuclear strength. We must continue to ensure that our military deterrence is sufficient to remove the temptation for them to use their undoubted strength against us, whether politically or militarily.

Moreover, we have to face the truth, unpalatable as it may be, that the continuing growth in the military strength of the Soviet Union is likely to be a problem which will be with us for many years to come. We should plan our own defences accordingly. Sudden ups and downs in our defence expenditure in response to changing economic conditions makes sense neither in respect to the defence needs we have to meet nor in respect to the most economical use of resources. What is needed is a steady reliable effort planned over a term of several years.

I realise that the current economic difficulties which allied countries are experiencing have their repercussions on attitudes towards defence budgets. However, economic considerations in no way affect the growth and modernisation of Warsaw Pact forces. To be credible, our deterrent posture should not be looked at in isolation but in relation to the military might of the Warsaw Pact.

Judged against this background, there is room for improvement in the present performance both of the Alliance as a whole and of individual allied countries, for among the allies there are some who do more, and some who do less.

In saying this, I am not advocating vast increases in defence expenditure by the West. What I am saying is, first, that there should be no unilateral cuts in force levels outside the context of an agreement with the Warsaw Pact on the MBFR. Secondly, there should be a continuing resolve to provide the resources needed to maintain an adequate contribution to Western defence - adequate in relation to the kind of military threat we can see, and adequate, too, in relation to our economic capabilities. On top of this, we must also try to find ways of stretching the effectiveness of every dollar spent on defence.

It is perhaps not always realised how much progress has already been made in this respect, through such measures as rationalisation and standardization. Important measures have been taken in several areas in halting the proliferation of weapon types among NATO forces, and in initiating coordinated efforts to achieve commonality in next generation systems, as well as improving the interchangeability of ammunition, fuel and other critical supplies.

Proliferation has been significantly reduced, for example, in anti-tank guided missiles and rockets and in short-range air defence systems. Alliance-wide coordinated efforts are underway or planned for the next generation of anti-tank weapons, surface-to-air missiles and anti-ship missiles. By the 1980s the new NATO artillery guns will have standardized characteristics so that their ammunition will be almost completely interchangeable. The prospects for standardized ammunition for infantry small arms are very encouraging; there is a serious possibility of fully interchangeable ammunition for future tank main guns; and main propulsion fuel for most NATO naval ships will be completely interchangeable by 1980.

This is encouraging. But much more remains to be done. In recent months there has grown up a much greater realisation of the need for a more resolute approach. At the Ministerial meetings of the Alliance held in December last year, Ministers agreed that these questions should be pursued by the NATO Council. They also agreed to form an Ad Hoc Committee under the Council to prepare a specific programme of action covering interoperability of military equipment. I can assure you that the Alliance will press ahead with those consultations with a full sense of urgency.

I am aware that there is a current of opinion in the West which would question whether we are really certain enough about the Soviet threat to justify all these efforts of defence by the Alliance. To a large extent, the facts themselves answer any such doubts. There is no question about the steady and massive expansion of Soviet military strength in virtually all respects. Nor is there any question about the active ideological hostility of the Soviet Union to the West.

It is, of course, true that we cannot be absolutely sure that, if the West abdicated the credibility of their deterrent strength, the Soviet Union would intervene against members of the Alliance either by direct military force or by political pressure based on the implicit or explicit threat of military force. This is not something that can be proved scientifically before the event. It is never possible to be completely sure about the intentions of another individual, let alone another government. But, in the words of Samuel Butler, "Life is the art of drawing sufficient conclusions from insufficient premises". And there is certainly evidence, enough hard facts, to make Soviet intervention in such circumstances of Western weakness at least a real possibility. Many would put the degree of likelihood much higher than that. But even if we accept, for the sake of argument, that Soviet intervention would be only one possibility among several, is it not still essential to ensure that it never becomes a reality? Because if we based our policy on the hope that the Soviet Union would restrain itself from exploiting opportunities to intervene, and if events subsequently proved our hope to have been unfounded, then we would have no way of retrieving our position, except perhaps through nuclear war.

Surely no responsible person in the West could contemplate such a grim risk. Surely it is the most obvious common-sense to pay the necessary premium to insure ourselves against such an appalling eventuality. And when we see what is at stake, it is, after all, a modest premium which allies are called upon to pay. Certainly, the average cost per head of population among Alliance members is well below that which certain isolated armed neutrals pay for what is in any case a much less effective security policy.

Search for common ground

I have been discussing the first part of a double pronged approach by the West to relations with the East, the need for an adequate deterrent in order to safeguard the security of the Alliance. I put this first because I consider it to be of prime importance. It is an essential condition for the second part of the approach, the pursuit of policies designed over a period of time to moderate Soviet conduct.

It is clearly essential that both West and East should attempt to find whatever common ground exists. We must explore every possibility of creating and consolidating mutual interests. We must be ready to negotiate on specific issues and keep open all available options for settling disputes. This combination of readiness to negotiate and readiness to restrain Soviet expansionism whenever necessary, offers the best hope for a gradual rapprochement over the years ahead. Indeed, it is this course which the West have resolutely been following in recent discussions with the East on such subjects as the CSCE, MBFR and SALT.

The short-term goal of SALT is to place a constraint on strategic weaponry, and the longer-term one is to achieve a reduction of the offensive strategic capabilities of the Soviet Union and the United States. As a result of the 1972 treaties limiting defensive systems, and the Vladivostok arrangements placing ceilings on offensive systems, a certain success for the short-term goal has been achieved.

Through the MBFR talks1 we are attempting to achieve a more stable military relationship in Central Europe at a lower level of forces. In the MBFR negotiations, the basic problem stems from the large superiority of Warsaw Pact ground force manpower and tanks in Central Europe. In our view, this is the main destabilising factor in the area. From the start of the negotiations the basic position of the participating Western Allies has been that MBFR should result in the establishment of approximate parity in ground force manpower in the area, in the form of a common ceiling, and that the disparity in tanks should be reduced. Last December, in the hope of generating movement in the negotiations, the participating Western Allies tabled an additional proposal in Vienna offering the inclusion of certain nuclear elements in MBFR, provided that the Warsaw Pact accepted the basic Western position, including the common ceiling and the withdrawal of a Soviet tank army. Although the East has criticised this latest proposal, it remains very much under discussion with the Warsaw Pact in Vienna and we shall continue to press for its acceptance.

In the wider field of East-West relations, last year saw the conclusion of the CSCE negotiations. For all its imperfections, the Final Act of Helsinki contains provisions of importance to the West, especially in humanitarian questions. Its ultimate significance will depend on the degree to which the promises of Helsinki are translated into reality. So far the auspices are not encouraging, but it is still early days, and the West have to continue to press strongly for implementation by all participants.

It is essential in all these negotiations that the allies maintain a high degree of political cohesion so that they speak with a united voice in any dialogue with the Warsaw Pact. The excellent cohesion achieved among the West in the CSCE negotiations, and currently in the MBFR talks, has been of immense value in strengthening the hands of Western negotiators. It is perhaps not sufficiently widely known that the machinery of political consultation at NATO Headquarters has played a significant role in achieving this high degree of coordination. In particular, the negotiated policies of all allied participants in the MBFR talks are hammered out within NATO.

I am sometimes asked about coordination among the members of the European Community and the rest of the Alliance. In my opinion, the movement towards greater European cooperation and unity is an essential condition for the reinforcement of the Alliance. I welcome the call in the recent report by the Belgian Prime Minister, Mr Tindemans, for continuing advance towards political as well as economic unity among the Nine. I also warmly welcome his realistic recognition of the fact that it is the Atlantic Alliance which gives Europe its security and stability and that there is little prospect of a common European defence policy in the near future. This is indeed true. Not that this fact in any way diminishes Europe's defence role, or the need to strengthen the European contribution to collective defence within the Alliance framework. But Western Europe alone will not in the foreseeable future have the power to defend itself, or to deter an attack from any major power.

While this situation remains, the United States has an indispensable role to play in European and Atlantic security, indeed a paramount role. This means that defence must be seen by all members of the Alliance as a collective task, with a common strategy and with common procedures to implement it. In the political field, it means that recognition of the intimate interdependence of members of the Alliance must be in the forefront of the formulation of policy by all allied governments. It means that, even though separate attention may be given by Western European members to their own special interests and problems, they must accept the essential need to provide for the overall security of the Alliance on an Alliance-wide basis. All this calls for a continuing hard effort of coordination within the Alliance. And I have every confidence that the will is there to make it succeed.

Need for informed public

I have stressed the long-term nature of the threat posed by the Soviet Union and the need, therefore, for a consistent long-term response, both military and political, from the West. This will only be possible if Western governments and public opinion recognise the need to maintain a strong and firm position over a long period of time.

It is here that the existence of a fully informed public opinion becomes so important. One of the great advantages enjoyed by the West over totalitarian regimes is the power for renewal inherent in the democratic way of life. However cumbersome the democratic process may be, it is nevertheless the political system with the greatest potential for creative rejuvenation. Only through the continuous consideration of opinions and ideas between contesting political forces can society, in the long run, be saved from stagnation. But equally, we should recognise that these democratic processes demand a special effort to ensure that the political debate is conducted in the full understanding and awareness of the realities of the situation. It is not enough to say that public opinion will reach the right decisions once the dangers are clearly apparent. We must ensure that this occurs in good time for effective remedies to be taken.

The prime responsibility for giving a clear and firm leadership to public opinion rests with member governments. But they can only respond effectively if they have the support of all those with opportunities to influence public opinion in their countries. This is more than the few who hold positions of power. For the support needed by member governments is wider than that of a top elite. It must be broad-based and permeate all sections of society.

I am sure that the readers of NATO Review will recognise that they have a significant role to play in ensuring that the policy I have described – readiness to negotiate and readiness to restrain Soviet expansionism whenever necessary – is properly understood in their countries. For no flattery is involved in saying that the readers of NATO Review are likely to number among those who most clearly appreciate the character of the situation we all face. And they can make a real contribution to the continuing security of the Alliance by spreading this information as widely as possible.

We must convince our people that we are doing our utmost to maintain peace. And we must convince them that our efforts can only succeed if they are based on political cohesion and on military strength of a scale sufficient to resist military or political pressures. Then we shall be able to face with confidence the constant challenges which we must expect to be our lot over the months and years ahead.