Exactly one year ago US Vice President Joe Biden spoke at the Verkhovna Rada, Ukraine’s Parliament. He talked about the historic chance offered by the Maidan revolution, the conflict with Russia and the desperate need for the country to reform. During his speech, one topic came up again and again: the need to fight corruption. Biden underlined the devastating effect of corruption on the country and its reform process. He also judged the “cancer of corruption” to be a threat on a par with the Russian aggression. His message was clear: if Ukraine wants to be successful in establishing a democratic system, the fight against corruption has to be taken seriously.

The United States, the European Union and other donors pledged to support Ukraine in this fight – both in spirit and in funding. Yet, the history of international efforts against corruption does not necessarily inspire hope for the success of the Ukrainian anti-corruption campaign. Very much as we have seen with the history of cancer, looking for and promoting some universal cure was the wrong way to go. Countries like Estonia, which have managed to evolve, did it by taking their own paths, alongside or even going against international standardised advice.

Assessing anti-corruption tools: trying to get to lessons learned

After over 20 years of international efforts against corruption, the question remains: how do we build societies based on universalistic values, where the distribution of public goods does not depend on political or economic connections. Since the successful state-building of the United States, largely attributed to the ‘intelligent design’ included in The Federalist Papers, the world has been haunted by the idea that good government is the by-product of smart legislative design.

US Vice President Joe Biden addresses deputies at the parliament in Kiev, Ukraine, 8 December 2015. © REUTERS

‘Constitutional engineering’, as this state-building endeavour was labelled by Giovanni Sartori, has been going on for more than a century now – even the soberest assessments of its success have not managed to relent these efforts. A flurry of reforms around the world was meant to create ‘good’ government, in other words a government both effective and virtuous. A special and more recent brand within this broad and well-established attempt is anti-corruption itself: the introduction of legislation meant to protect public integrity and control corruption.

Several international conventions – the African Union Convention, the Inter-American Convention, the Convention of the Council of Europe and, most notably, the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) – outline a set of instruments aimed to rein in particularism.

UNCAC was first signed on this day, 13 years ago. With 140 signatories it is recognised as a standard-bearer of anti-corruption efforts in the world. It promotes, for instance, the establishment of a dedicated anti-corruption agency, one of the main institutional recommendations proposed by the international community to date. Donors and governments persistently recommend the creation of such an agency as an important piece of a country’s institutional architecture and its large-scale anti-corruption strategies. But, do such legal instruments really do the trick? Do they lead to a reduction in corruption?

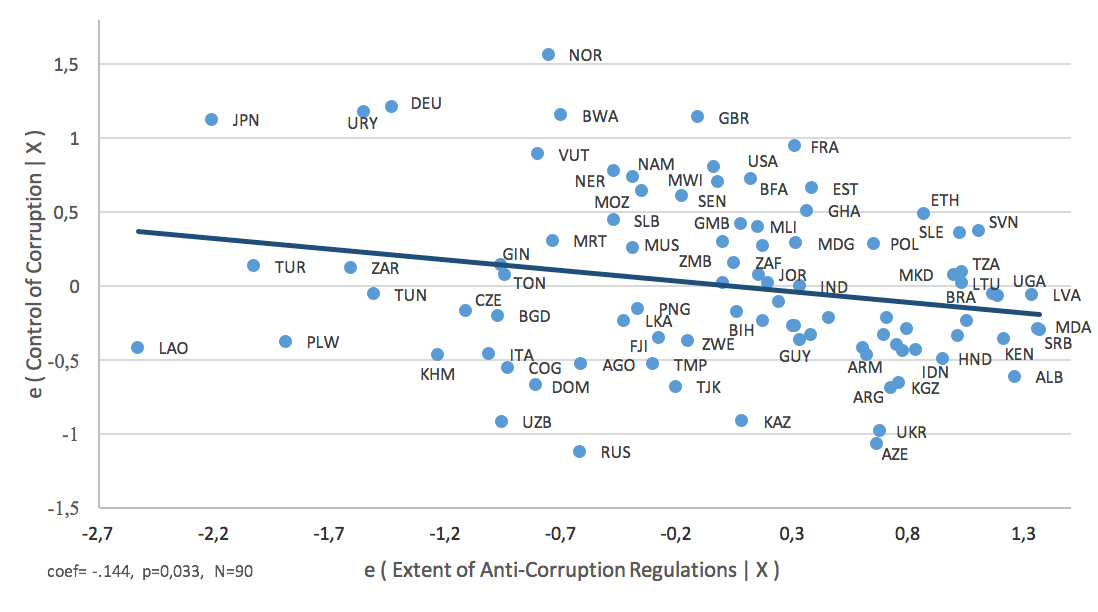

Graph 1 – “Figure 1: Anti-corruption legislation and control of corruption, data sources: Worldwide Governance Indicator on the Control of Corruption; own calculations on the extent of anti-corruption regulations".

In the past five years, the EU-funded ANTICORRP project set out to assess the success of anti-corruption efforts. With the project coming to an end, we are happy to report some of the results of our analyses – even though they may appear somewhat disheartening.

Take for example the relationship between the overall extent of legal regulations and control of corruption. We tested it using an index combing indicators of political finance, financial disclosure and conflict of interest regulations with the presence of a dedicated anti-corruption agency and an ombudsman office. A high score on this index would indicate a country with a comprehensive legal framework for the control of corruption, by all international standards. Yet, the relationship between the extent of anti-corruption legislations and measures for the control of corruption proves to be negative (Figure 1). A high amount of legislation is associated with not less, but more corruption.

Naturally, we also looked at the effectiveness of each of the classical anti-corruption instruments. We first considered the introduction of an anti-corruption agency and ombudsmen. Tracking progress over several years, we did not find any significance. Corruption scores before and after the adoption of these instruments did not change.

Next we assessed restrictive rules on party finance, proposed in particular by the European Commission and the Council of Europe Group of States against Corruption. Some post-communist member states, such as Bulgaria, Croatia and Latvia, but also Greece and Italy have numerous tight formal regulations of political financing but at the same time do badly on the control of corruption scores. Meanwhile, the Netherlands and Denmark – older, more consolidated democracies – have little such regulation, yet better control of corruption.

These tendencies were confirmed in quantitative analyses using both global and European data. Legal restrictions on party finance do not reduce corrupt practices – they might even prompt more illegal behaviour. While historically such reforms were successful in Britain, we were unable to find contemporary cases where corruption was curbed due to party finance reforms.

Anticorruption Policies Revisited: Global Trends and European Responses to the Challenge of Corruption

Running these econometric analyses returned clear results. We further tested financial disclosure and conflict of interest regulations, which try to prohibit public officials from participating in any number of activities that may be seen to compromise their impartiality. Officials are obliged to disclose such potential conflicts and are limited in the assets or additional appointments they can hold, what gifts they can accept and in which situations they need to withdraw themselves from decision-making processes because decisions might touch upon officials’ private interest. Data on conflict of interest regulation mirrored the situation of party finance.

When controlling for socio-economic development we found that more corrupt countries tended to have more comprehensive and strict regulations. Financial disclosure regulation for public officials also did not proved to be very effective. Their effect on the control of corruption was so minimal, we could not consider it significant. Only when associated with freedom of the press did they start to matter. Public private separation and conflict of interest are certainly necessary to good governance, but this seems to stem more from how a state is organised and a society sanctions them at reputation level – simply adopting rules against conflict of interest will not work when opportunities are rife and normative constraints low to none.

The situation finally proved different when we looked at tools that specifically promote government transparency. While the adoption of a freedom of information act did not prove to be significant except when associated with a numerous and active civil society, we found that budget transparency (as measured by the Open Budget Index) was significantly correlated with better control of corruption.

Public Integrity: Context Matters

So, generally speaking, the news is not good. Most simple tools promoted by the international anti-corruption efforts do not seem to work. Building on many years of empirical research the explanation we offer for this is neither new, nor complicated. Context matters. Generally, however, this does not refer to a country’s constitutional framework, none of each seems to matter.

Instead, we found quite down-to-earth issues to be significant. Besides fiscal transparency, these were the absence of red tape, more trade openness, independence of the judiciary, Internet access and associativity as measured by number of Facebook users per country.

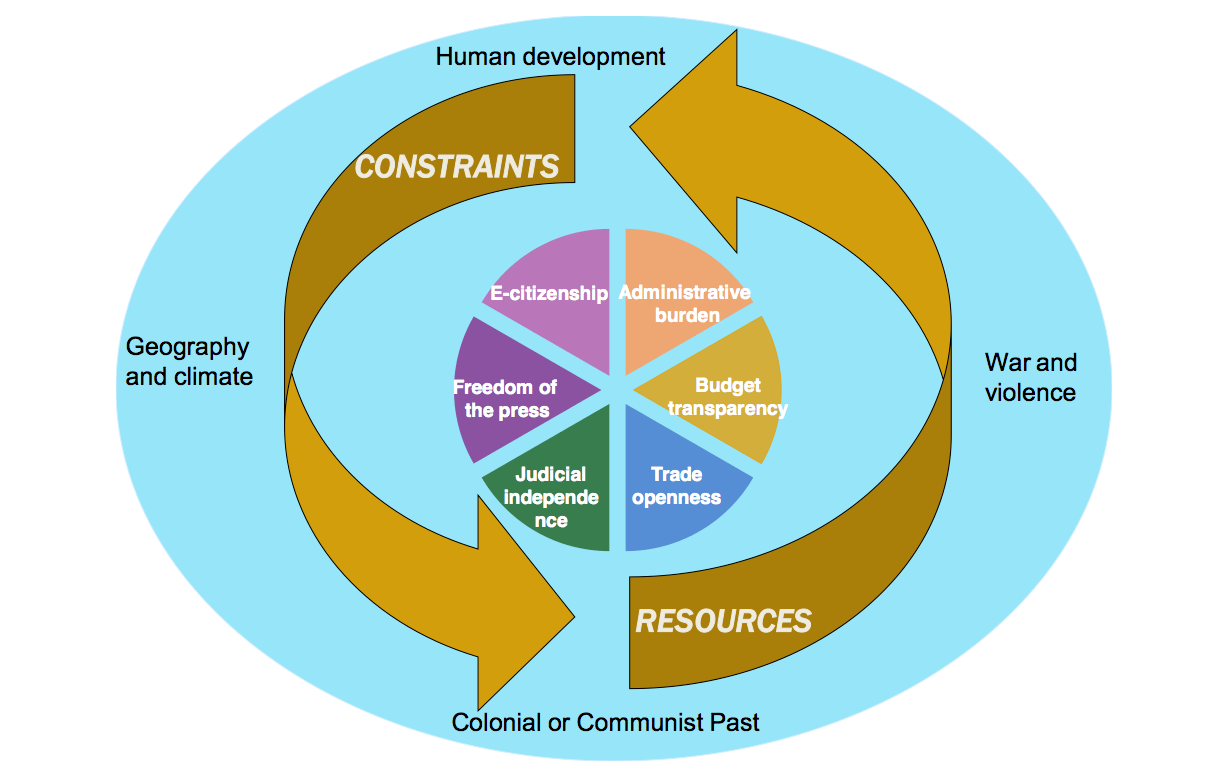

In our previous work we have grouped these into factors generating opportunities for corruption (power discretion, excess regulation and bureaucracy, competition restrictions, unaccountable material resources such as foreign aid, natural resources etc.) and factors creating constraints on the spoilers of public resources, such as independence of the judiciary and collective action capacity of citizens1.

We equally tested indicators for these factors against the control of corruption and found them to be positively correlated. This suggests that a mechanism exists for controlling corruption which cuts across state and society, a balance between resources and constraints grounded in the broader development context but also generating a specific policy context, as illustrated in figure 2. We subsumed this framework into a new Index of Public Integrity which measures public integrity frameworks through objective and actionable data2.

Having established these contextual factors, we tested the anti-corruption instruments yet again. We wanted to see whether they fail our hopes in general or do better in certain societal contexts. Our focus was in particular on those societal factors, which could enhance and support the potential effect of anti-corruption regulation.

Testing anti-corruption tools

Judicial independence appeared to be particularly important throughout our analysis, but unfortunately there is no silver bullet here either. No specific form of organisation of the judiciary is conducive to independence, which is rather the result of social pluralism. The elite in government and the elite in judiciary should ideally come from different backgrounds and not have entirely aligned interests if horizontal accountability is to work and collusion is to be avoided. Also, strong civil society within the judiciary and the legal profession is needed to prevent the judiciary from being corrupt itself.

The one tool that worked in our initial analysis was budget transparency. We tried to see under what circumstances this transparency translates into accountability. In this context two factors proved to be especially significant: freedom of the press and e-citizenship. A country with good scores on these indicators benefitted more from disclosing its budget. Particularly the interaction between those factors proved to be significant.

What does this tell us? Public scrutiny is what makes fiscal transparency truly work. Societal participation can make up for a lack in official oversight and for a situation in which auditors, police and magistrates do not play the role they are supposed to play.

Changing the anti-corruption agenda

The lesson coming from all this is clear. We need to rethink the way we do anti-corruption. Instruments that were promoted for years do not work the way we expected them to. They only work under certain societal conditions. We therefore have to move away from thinking of anti-corruption as a blueprint that can be applied anywhere.

Solutions need to be localised and adapted to individual country contexts. We do not need more regulation, but smart regulation that is adapted to local conditions and a reduction of rent opportunities provided by regulation, even regulation meant for good governance. If the international community is serious about fighting corruption, in Ukraine and elsewhere, it may need to cut more laws, not add more.

We will not get anywhere by using the same tactics as in the last twenty years. Successful examples include Chile with its audit agency which is at the same time ombudsman and reviews all legislation, or Estonia with its streamlined minimal legislation and e-government. These are shining examples that a good control of corruption results from preventing corruption to happen in the first place. All you do after it has already happened matters far less.

An extended version of this article will be published in a special issue on evidence-based national integrity frameworks as Mungiu-Pippidi, A. & and Dadasov, R., “When do laws matter? The evidence on national integrity enabling contexts” in Crime, Law and Social Change, Spring 2017 (forthcoming). Most of the research presented here is based on results developed as part of the EU FP7 ANTICORRP Project, grant agreement no. 290529. The full name is Anticorruption Policies Revisited: Global Trends and European Responses to the Challenge of Corruption.

1 Outlined in Mungiu-Pippidi, A. (2015), “The Quest for Good Governance: How Societies Develop Control of Corruption,” Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

2 More quantitative evidence and details on the construction of the IPI was published in Mungiu-Pippidi, A. & Dadašov, R. (2016), “Measuring Control of Corruption by a New Index of Public Integrity” in European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, Vol. 22, Issue 3, pp 415–438.