What were the surprises in international security in 2012 - and what can we learn from them? Here, four experts ranging from a former UN Commissioner to the head of security think tank outline what the lessons learned of 2012 were.

Louise Arbour

Louise Arbour is President of the International Crisis Group. Prior to this, she served as the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

While perhaps not exactly surprising given the well-known split among its permanent members and the fallout from the intervention in Libya, the inability of the UN Security Council to address Syria in 2012 brought that essential international body to astounding new heights of fecklessness. With 60,000 killed in Syria and 2.5 million displaced, the world body entrusted with maintaining international peace and security is giving additional ammunition to its critics and urgency to calls for its reform.

Michael Brzoska, University of Hamburg

Professor Michael Brzoska is an economist and political scientist who heads up the Institute for Peace Research and Security Policy (IFSH) at Hamburg University

I had expected far more repercussions of the "Arab spring" in other countries of the Middle East as well as in other parts of the world. Unlike earlier "waves of democratisation", the citizen rebellions starting in Tunisia seemed to instigate few followers in Subsaharan Africa, Latin America, Central or East Asia, all of which have their share of authoritarian regimes. Even in the Middle East, I found it surprising that anti-regime activities in 2012 were restricted to few countries (with Syria being the most violent). This was in spite of the much better means of spreading news and information globally, compared to the global wave of democratisation in 1990/91, and in spite of the successes of rebellions in Tunisia, Egypt and Libya.

The reasons for this lack of diffusion of rebellion are unclear to me. Possibly the global economic crisis overshadowed people’s concerns about their political systems in many parts of the world. Or democratisation may not seem as attractive in 2012 as it was two decades earlier. If that is the explanation, it would question a major foundation of Western security thinking.

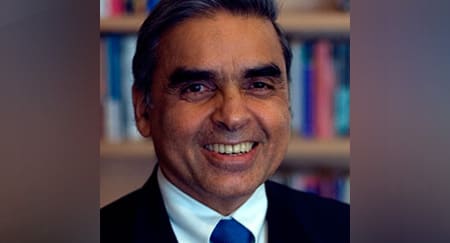

Kishore Mahbubani

Kishore Mahbubani is Dean of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, NUS, and author of ‘The Great Convergence: Asia, the West, and the Logic of One World.

The failure of ASEAN to agree on a joint communiqué at the ASEAN Ministerial Meeting in Phnom Penh in July 2012 was a big shock. This was the first time in 45 years that ASEAN has failed. But the failure could well prove to be a blessing in disguise.

ASEAN will now be affected by new competition between the USA and China. The failure in Phnom Penh provided the first signal that new great power competition is returning to South East Asia.

Giles Merritt

Giles Merritt heads up the Brussels-based think tanks Friends of Europe and Security & Defence Agenda. He was previously a journalist for the Financial Times.

The European Commission’s failure to champion the €37.5 billion merger of Franco-German EADS, owner of Airbus, and the United Kingdom’s BAE Systems was the biggest surprise to me.

The integration of the two high-tech aviation and avionics leaders had looked like an EU-inspired blueprint for industrial success. For several years, EU leaders have been urging the consolidation of Europe’s defence industries, so the proposed deal – which originated in the corporate boardrooms of EADS and BAE Systems – looked like an answer to its calls. Yet both the Commission and the European Parliament kept silent and withheld the political support that might have ensured that the deal went through.

It was a bizarre coincidence that the merger’s collapse came on the day that the Commission unveiled its new industrial strategy for regaining Europe’s competitive edge in the face of Asian and North American competition. One of the most powerful arguments for the EADS-BAE marriage had been the expectation of industry analysts that within 20 years China will challenge Airbus and Boeing in the global aviation market, while also creating a powerful new defence industry. That scenario now looks all the more likely.

The EU’s executive body is meant to be the driving force behind Europe’s efforts to revive laggard industries and the continent’s fight to reverse the long-term economic decline that the eurozone crisis appears to presage. In all likelihood, the end of the EADS-BAE merger will be no more than a footnote in the history books. But it may mark the point when the European Commission openly acknowledged that it has become little more than a secretariat to EU governments. That is a far cry from the political powerhouse that some Europeans fear – and for which others still hope.

Read also:

[a CMSref=/2012/Predictions-2013/Impact-security-2013/EN/]Which issue do you feel will have a significant impact on security in 2013 and why? »[/a]