Global terrorism is cheap, requires little manpower, captures the world’s attention and gives the weak the ability to terrify the strong. Is there any way to beat it? Here Bjorn Lomborg sets out some of the cost problems - and offers some possible solutions.

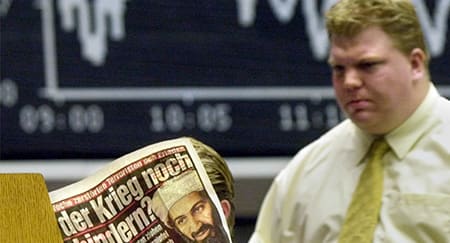

The fruits of fear: the plane crashes of September 11 intended to bring stock market crashes soon after © AP / Reporters

Is this how it starts? Poverty, disease and hopelessness are seen by some as perfect ingredients for recruiting future terrorists © Reporters

The material cost of a suicide bombing is as low as US$150. This modest investment will result in an average of 12 deaths and spread fear throughout the targeted population.

The developed world is responding to the threat of fundamentalist Islamic terrorism by building ever-bigger, ever-better fortifications around key targets. Entry to airports and embassies is more difficult; key landmarks are blocked from potential bombers.

Since 2001, the world has spent about US$70 billion on increased homeland security measures. Predictably, this has reduced the number of trans-national attacks by about 34 per cent. However, on average, terrorism has claimed 67 more deaths each year.

The rise in the death toll has occurred because terrorists are responding rationally to the higher risks imposed by greater security measures. They have focused on plans that create more carnage.

Research recently commissioned for the Copenhagen Consensus project concludes that target nations are overspending on measures that shift the risk of attack instead of reducing it.

As research author Todd Sandler argues, terrorists behave with chilling predictability. Actions by governments to guard one venue simply prompt the terrorists to shift to another target.

Installing metal detectors in international airports in 1973 led to an immediate and prolonged drop in skyjackings. At the same time, however, there was a significant and large increase in hostage-taking and other incidents that resulted in more deaths. Building metal detectors had the unintended consequence of more bloodshed.

To be effective, counterterrorism measures must either make all modes of attack more difficult or reduce terrorists’ resources

Similarly, fortifying US embassies this decade led to more assassinations and attacks against embassy officials in non-secure venues. Actions to protect officials shifted attacks to business people and tourists, such as in the Bali attack in 2005.

The increase in homeland security spending in the United States, Canada and Europe has produced more attacks against US interests in the Middle East and Asia, where there are softer targets and Islamic fundamentalists can rely on indigenous populations for support.

The policy message is simple: to be effective, counterterrorism measures must either make all modes of attack more difficult or reduce terrorists’ resources. The majority of today’s counterterrorism initiatives do neither.

Making some targets ‘harder’ simply encourages terrorists to shift their focus. Terrorists can observe how governments change potential targets and then attack accordingly. This was true of September 11, 2001, where Logan, Newark, and Dulles airports were viewed as poorly screened.

Increasing defensive measures worldwide by 25 per cent would cost another US$75 billion over five years. In the extremely unlikely scenario that attacks dropped by 25 per cent, the world would save about US$21 billion (see page 50 of the Copenhagen Consensus report on transnational terrorism for calculations). Even then, each extra dollar spent increasing defensive measures would achieve – at most – about 30 cents of good. Allowing for the most generous assumptions, this approach remains a poor investment.

Why keep spending – and why so much?

Countries maintain massive levels of spending in an area with such huge costs and so few benefits because of politics and extreme risk aversion. People naturally over-respond to catastrophic events with a very low probability of happening, instead of preparing for more certain events with small losses. Moreover, targeted nations are in a security race to deflect terrorist attacks onto foreign soil. This race will ultimately produce no winners.

Terrorists enjoy strategic advantages over the nations they attack. Terrorists can hide among the general population and are difficult to identify, whereas liberal democracies present a rich array of targets. Terrorists can be unrestrained in their attacks; governments must exercise self control. Perhaps the most essential asymmetry between the two, however, lies in the terrorists’ ability to cooperate – and in targeted nations’ reluctance to do so.

Dating back to the late 1960s, trans-national terrorist groups have collaborated in loose networks for training, intelligence, the provision of safe havens, financial support, logistical assistance, weapon acquisition, and even the exchange of personnel. They pool resources to augment their modest arsenals.

In contrast, targeted nations place a huge value on their autonomy over security matters. Sometimes they do not even agree among themselves on who the enemy is – until recently, the European Union did not view Hamas as terrorists. Despite different agendas, supporters and goals, many terrorists groups have the same two opponents: Israel and the United States.

Some 40 per cent of transnational terrorist attacks are directed at US interests, and some observers argue that the world’s sole superpower could do more to project a positive image and negate terrorist propaganda.

This could be achieved in part by reallocating or increasing foreign assistance. Currently, the United States gives only 0.17 per cent of gross net income as official development assistance – the second-smallest share among OECD countries. Aid is frequently skewed to countries that support the United States’ foreign policy agenda.

Efforts to expand humanitarian aid with no strings attached would allow the United States to do more to address hunger, diseases and poverty, while reaping considerable benefits to its standing and lowering terror risks.

A cheap solution?

On a wider international perspective, increased cooperation is difficult due to nations jealously guarding their sovereignty over police and security matters. Cooperation only works if it is comprehensive. If all but a single country denies terrorists a safe haven on their soil, the one holdout undercuts the efforts of the others.

But if the political will could be found, increased cooperation to cut off terrorists’ funding would be relatively cheap. This would involve extraditing more terrorists and clamping down on the charitable contributions, drug trafficking, counterfeit goods, commodity trading and illicit activities that allow them to carry out their activities.

Because terrorist attacks are so cheap to carry out, this approach wouldn’t necessarily reduce smaller events such as ‘routine’ bombings or political assassinations, but would significantly hamper the spectacular terror events that involve a great deal of planning and require serious resources.

The advantages would be substantial. Doubling the Interpol budget and allocating one-tenth of the International Monetary Fund’s yearly financial monitoring and capacity-building budget to tracing terrorist funds would cost about US$128 million annually. Stopping one catastrophic terrorist event would save the world at least US$1 billion. The benefits could be almost ten times higher than the costs.

Target nations must remember that the world faces many challenges that are, in many respects, more pressing than terrorism. The number of lives lost to transnational terrorist attacks since 2001 has been an annual average of 583, according to MIPT and US State Department figures. This is dwarfed by the death toll exacted by HIV/Aids, malaria, malnutrition or even traffic accidents.

Unlike other global challenges, attempts to combat terrorism can have significant unintended negative consequences. Strong offensive measures against terrorists can lead to backlash attacks as new grievances are created, whereas cooperating with their demands creates an incentive for others to mimic their tactics.

A terrorist group can, at times, be annihilated, but new groups will surface. Actions to kill a group’s leaders may result in more ruthless leaders replacing them, as Israel discovered with Black September and Hamas.

Terrorist attacks will always remain an obvious and cheap investment for groups who seek to spread panic and alarm. Each dollar spent by terrorists on the London transport bombings in July 2005 achieved an astonishing US$1,270,000 of damage (as the estimated damage of $2.5bn came from an operation that cost just $2,000).

The enemies of terrorism must respond surely and rationally to ensure that counter-terrorism spending achieves the most good possible.

Fear drives some nations to spend eye watering amounts of money constructing ever-bigger fences around potential targets. Building international cooperation and far-sighted foreign policies would have greater rewards.

The most effective responses to terrorism turn out to be the cheapest. Sadly, they are certainly not the simplest.