Robert Pszczel gives a personal account of how he has seen changes in the media over his professional career – on both sides of the Iron Curtain.

We all can see that the media has been changing rapidly over recent decades. But my own personal experience over the last 20 years has shown me the extremes of those changes - from old media Cold War journalist in the Soviet Bloc to new media NATO press officer in Brussels HQ.

Compare the following two snapshots. One, from 1988, takes me back to Warsaw. I recall an atmosphere of weakening (but still functioning) censorship applied to the Polish media. My work at a time in a daily newspaper brings back memories of raging debates about possibilities of real democracy associated with the reviving Solidarity movement – none of those really possible in official publications, but very much alive in underground press and at clandestine meetings.

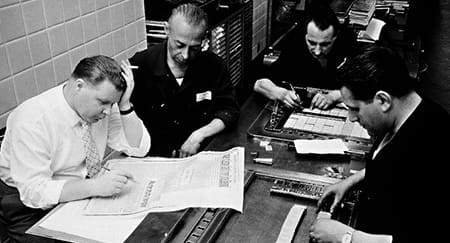

In a strange way, my most vivid recollections of that era centre around the routine problems, associated with the archaic state of “media infrastructure”, such as:

• the smell of lead in the printing office where morning editions were prepared, often with the use of rather rudimentary technology.

• the pleasures of typing out stories from foreign correspondents who dictated their daily products via a creaky telephone line.

• and the joys of picking up long and winding stretches of telex paper from the official news agency.

No internet, no mobile phones, no blackberries.

And what about informed public debate on foreign and security policy? Well, any mention of NATO - unless accompanied by a rigorous condemnation of this “war machine” - would send the censors into a rage. Local elections’ participation figures in towns with a significant military presence were not published so as not to give “the enemy” (NATO?) an insight into the armed forces dislocation patterns. Journalists trying to discover real figures for defence expenditure were told to find another subject, because such data was considered an official secret.

In short, trying to debate the merits of the latest Warsaw Pact communiqué was futile - and risky for your work prospects.

Any mention of NATO unless accompanied by a rigorous condemnation of this “war machine” would send the censors into a rage!

And yet, even then, in such an unfriendly environment, information flows were taking place. Some specialized publications printed professional evaluations of the latest defence technology trends. Colleagues coming back from trips abroad shared summaries of the most important articles appearing in Allied capitals. And some brave thinkers began visualizing possible security policy choices once the old regime had crumbled.

Those who could not wait for the freedom to analyze the present and forecast future military trends turned… to the past. Many fascinating commentaries were written of ancient battles and campaigns – with some very contemporary conclusions. I remember one historical piece on an Alexander the Great campaign that somehow made its way past the censor, even though its stinging critique bore an uncanny resemblance to the Soviet Army tactics used in the 80s.

Fast forward to 2008 and it’s like landing on another planet.

Now I do not have to worry about state censorship of my writings about security policy or NATO: in fact, I get paid for it! Poland, together with ten other former Warsaw Pact members, has integrated fully into NATO. And what a different NATO it is.

Now I do not have to worry about state censorship of my writings about security policy or NATO: in fact, I get paid for it!

Following its stabilizing efforts in the Balkans (which are ongoing, particularly in Kosovo), the Alliance’s attention is now hugely focussed on Afghanistan. This is how the media see it too. Media outlets (whether local, regional or international) cover the developments in great detail. Political commentaries, military analysis or stories of individual civilians and military involved in the Afghan mission provide a constant stream of news – published or broadcast.

My compatriots, like those in other ISAF contributing countries, follow these stories with huge interest. And – naturally – communiqués and official statements are not sufficient. Information is sought from websites, articles, photos, videos, audios from press conferences, iPod-friendly modules. Even blogs of people on the ground are the expected norm. And embedding journalists in military units often allows viewers/readers to follow security engagements directly.

A special challenge for a press service like ours is the high tempo of response to queries. Journalists are not prepared to wait too long for information and comments – the pressure exerted by 24 hour news channels and steeper deadlines (international press agencies are a case in point) puts a high premium on coordination and information sharing between the civilian components of NATO.

NATO’s press team meets these challenges. We know how high the stakes are. Tax paying publics need to know how their defence expenditure is being used. Misinformation can affect mission support. And we need to confront the spoilers, such as the terrorists, insurgents and Taliban, whose lies and scare tactics spread through new and old media. These need to be firmly rebutted.

One last observation. Most know that NATO deals with security missions, such as the ones in Afghanistan, Kosovo, a Mediterranean maritime operation and the training mission in Iraq. But NATO now also deals with a security challenges going well beyond the purely military. Cyber defence, energy security and the fight against terrorism all require substantial political, budgetary and technical components.

So, in spite of enormous geopolitical changes in Europe, and notwithstanding the breathtaking technological advances in the media world over the last two decades, one principle remains unchanged: international security news remains vital. There are many stories that still need to be told. Watch this space…