With a computer in virtually every home and office, the chances for mass communication are better than ever before. But how well protected are we if that communication is malicious or hostile? Johnny Ryan makes the case that iWar attacks could be the most innovative form of warfare since the invention of gunpowder.

Long shelf life: Trojan horses are still being used in modern warfare (© Science Photo Library / Van Parys Media )

A short time from now it is likely that “iWar”, a form of internet-based warfare, will erupt across the globe.

This form of warfare’s potency will grow as economies, governments, and communities close the so-called “digital divide”. Those embracing the internet most will be increasingly vulnerable to iWar attacks which exploit the consumer infrastructure.

iWar will proliferate quickly and can be waged by anyone with an internet connection who can follow simplified online instructions. The trend of increasing vulnerability, coupled with the convenience and deniability of attack, is likely to result in a conflagration of iWar waged by individuals, communities, corporations, nations and alliances. Its impact could be enormous, and NATO members have little time to consider an effective response.

What is iWar?

iWar is distinct from what the United States (US) calls ‘cyber war’ or from what China calls ‘informationalized war’. These refer to sensitive military and critical infrastructure assets, and to battlefield communications and satellite intelligence. China’s December 2006 Defence White Paper, for example, refers to the importance of gaining supremacy in space to control information assets such as satellites.

It refers to attacks carried out over the internet that target the consumer internet infrastructure, such as the websites providing access to online services.

In contrast, iWar exploits the ubiquitous, low security infrastructure. It refers to attacks carried out over the internet that target the consumer internet infrastructure, such as the websites providing access to online services. While nation states can engage in “cyber” and “informationalized” warfare, iWar can be waged by individuals, corporations, and communities.

For an example of iWar, take Estonia, 27 April 2007. A blizzard of distributed denial of service (DOS) attacks hit important websites. This continued until mid-June. The website of the president, parliament, ministries, political parties, major news outlets, and Estonia’s two dominant banks were all hit.

Just one day before the attacks started, a bronze statue commemorating the Soviet liberators of Tallinn was cordoned off, and removed two days later.

Estonia's Defence Minister called the attacks ‘a national security situation. It can effectively be compared to when your ports are shut to the sea’.

How does iWar work?

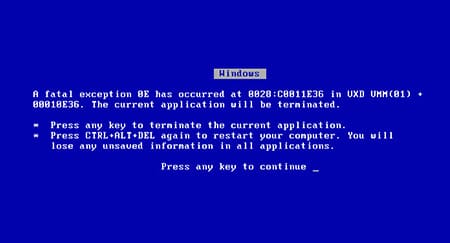

A denial of service (DOS) attack bombards a high volume of information requests to overwhelm a computer or networking system on the internet. This can render the system unable to respond to legitimate requests, which could include providing access to a particular website. DOS attacks have existed in various forms since at least as early as the “Morris Worm” in 1988.

iWar is distinct from what the US calls ‘cyber war’ or from what China calls ‘informationalized war’

A distributed denial of service (DDOS) attack operates on the same principle. But it multiplies its impact by directing a “botnet” of networked computers that have been remotely hijacked to bombard the target system with many requests at the same time.

Botnets can be controlled by a single individual. Some botnets in the attacks on Estonia included up to 100,000 machines.

The new internet networking standard, IPv6, which was initially expected to mitigate many security risks, may in fact increase vulnerability to DDOS attacks.

What makes iWar likely?

I suggest that five characteristics of iWar indicate that it has the potential to revolutionize conflict, including its

[UL][LI]potential to extend the franchise of offensive action;[/LI]

[LI]geographical reach;[/LI]

[LI]deniability;[/LI]

[LI]ease of proliferation; and[/LI]

[LI]impact on “e-ready” targets.[/LI][/UL]

Taken together, these characteristics suggest that the advent of iWar may mark a new military revolution on a par with the adoption of gun powder or the Napoleonic levee en masse.

First, like the early matchlock musketeer, the iWar attacker is equipped with cheap, powerful technology that requires only a modest amount of training. iWar can extend the franchise of offensive action to an unprecedented number of amateurs, whose sole qualification is their connection to the internet.

Second, iWar is unhindered by the expense and effort that often accompany offensive action against distant targets. Conventional kinetic offensive technology relying on physical assets is not only expensive, but also comparatively slow. While its damage is unconventional, iWar belligerents can inflict quick damage from anywhere, on anywhere, at virtually no cost.

Third, iWar is deniable and difficult to punish. Today it is still unclear whether the Estonia attacks were a “cyber riot of hacktivists”, or whether they were officially sanctioned. Even if official culpability could be proven, it is unclear how one state responds to an iWar attack by another.

Nor would a criminal investigation be less problematic. Even if digital forensic investigation could trace a malicious botnet to a single computer that is commanding a DDOS attack, prosecution could be hampered by the computer being in another, uncooperative jurisdiction. And even if cooperation were forthcoming, the computer might have been operated from an internet café or another anonymous public connectivity site.

Fourth, iWar’s proliferation is not limited by the communications constraints on earlier military innovations. Gun powder took centuries to proliferate from China in the seventh or eighth century. But in the 2007 DDOS attacks on Estonia, web forums quickly disseminated idiot guides on how to participate in the attack.

Finally, the impact of iWar attacks will increase as the internet increases its important role in daily political, social, and economic life. Services will continue to migrate to online interaction with customers. In Estonia, which was ranked 23rd in the 2007 e-readiness rankings, there are almost 800,000 internet bank clients in a population of almost 1.3 million people, and 95 per cent of banking operations are conducted electronically.

In the United Kingdom, expenditure on internet advertising has now eclipsed advertising in national newspapers. Internet delivery of media content now competes with conventional distribution of newspapers and music, and television content will soon follow.

Business organizations are likely to become increasingly dependent on internet technologies in their internal operation by using internet based applications such as Google “docs & spreadsheets” to replace conventional packages such as Microsoft Office. So iWar threatens not only interactions between organizations and their clients, or between state and citizen, but also the internal operations of organizations.

What’s the response?

No single state has complete control over the internet. It is a universal resource - like the seas. Protective policy in the past prompted the development of new international norms of behaviour, such as informal customary laws to protect access to the sea. The question remains whether a similar legal framework will evolve to protect access to the internet in the long term.

The Comprehensive Political Guidance adopted by NATO heads of state and government in November 2006 includes 'the ability to protect information systems of critical importance to the Alliance against cyber attacks' among its capability requirements in the next decade and a half.

While its damage is unconventional, iWar belligerents can inflict quick damage from anywhere, on anywhere, at virtually no cost

Sharing information at NATO level will allow for early warning of suspicious activity and profiling of possible iWar attacks. Some NATO members have already moved to protect themselves from internet age threats by establishing national Computer Emergency Response Teams (CERT).

Coordinating these CERTs at NATO level, in cooperation with the European Union, would be a useful step to limit the impact of iWar attacks in the short term. For example, if an attack on a Czech website by a user on a French network is detected, the Czech CERT can request its French counterpart to cut the connections used in the attacks.

The Estonian example illustrates the need for immediate action. The Estonian CERT was only established in 2006, and many governments have yet to establish their own CERT teams.

What iWar means for NATO countries…

The advent of iWar reflects the trends of the new century: the spread of the internet, its empowerment of individuals, and the relative decline of the power of the state to control the communications infrastructure. Online instructions and the necessary software empowers virtually any actor with internet connectivity to attack distant enemies.

The two trends of increasing vulnerability and ease of attack make conflagration of iWar likely. In the short term, iWar poses a gathering threat to NATO members by empowering both lower level actors and unfriendly governments. It remains to be seen whether iWar becomes a tool of state actors alone or the whether lower level actors are maintain their ability to leverage iWar against nation states.

Since an international consensus is unlikely to emerge and articulate accepted legal norms for some time, NATO must approach the problem as an immediate threat and strive to develop practical defensive cooperation.