At their Istanbul summit in November 1999, the leaders of 54 states participating in the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe signed the Charter for European Security. The Charter originates in a debate launched in March 1995, largely to calm Russian concerns about NATOs eastward enlargement on developing a Common and Comprehensive Security Model for Europe for the 21st Century. The initial debate was rather abstract and soon stagnated. But it was given a new lease of life in December 1997, when ministers meeting in Copenhagen agreed to draft this new pan-European security document. Victor-Yves Ghebali assesses the significance of the Charter and its relevance for NATO-OSCE relations.

The OSCE Charter for European Security may not be revolutionary in nature but it should not be regarded as a mere empty shell. It reviews the new risks and challenges to security on the European continent in the post-Cold War strategic environment, reaffirms some basic general principles and provides for the strengthening of the OSCEs operational capacities in conflict prevention, crisis management and post-conflict rehabilitation. Finally, in the appended Platform for Cooperative Security, the Charter proposes a set of arrangements for closer ties and cooperation between the OSCE and other international institutions, which together with the operational guidelines for a more effective OSCE are directly relevant to NATOs new role in Europe.

The Charters main elements

Risks and challenges: The OSCE states originally intended to compile a comprehensive list of the risks and challenges to security in Europe. Gradually, they realised that this would not be feasible because of difficulties in clearly differentiating between external and internal threats in an evolving security environment. Accordingly, the Charter sets out only a limited number of security risks, including international terrorism, violent extremism, organised crime, drug trafficking, the spread of small and light weapons, acute economic problems, environmental degradation, as well as instability in the Mediterranean basin and central Asia.

There is no specific mention of the security rights of states that are not part of a military alliance. The issue of the possible deployment of nuclear weapons in states that are at present non-nuclear is not addressed either. In this respect, the Charter has fallen short of Moscows expectations. It also unambiguously reaffirms the inherent right of each OSCE state to choose its own security arrangements, including treaties of alliance. At Russias request, the Charter does stress that within the OSCE no State, or group of States or organisation can have any pre-eminent responsibility for maintaining peace and stability in the OSCE area. But the same provision adds or can consider any part of the OSCE area as its sphere of influence clearly an allusion to the Russian concept of the near abroad.

OSCE structures: The Charter did not renew the mandate of the Security Model Committee which had been set up specifically to draft the Security Charter contrary to Russian wishes. More importantly, it refused to envisage an institutional overhaul, since the overwhelming majority of governments feel that the OSCE should not depart from its traditional pragmatism and flexibility. Consensus has been upheld as the basis for OSCE decision-making. But it was decided to improve the OSCE Permanent Councils notoriously unsatisfactory decision-making procedures. Under these arrangements, to save time, smaller states were only consulted at the very last moment, when the Permanent Councils decisions were on the point of being formally adopted. A new informal, open-ended body will now meet as the Permanent Councils Preparatory Committee.

Humanitarian dimension: One normative development concerning the issue of national minorities is worth mentioning. In paragraph 19 of the Charter, the OSCE governments unexpectedly recognise that respect for human rights, including the rights of individuals belonging to national minorities, is not just an end in itself but also a means to strengthen the territorial integrity and sovereignty of states. They also acknowledge that one way to preserve and promote the ethnic, cultural, linguistic and religious identity of national minorities within an existing state is to provide them with a degree of autonomy.

Strengthening the OSCEs operational capacities

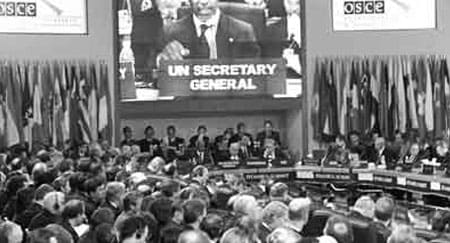

UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan appears on overhead screens as he speaks dur-ing the opening ceremony of the OSCE summit in Istanbul, Turkey 18 November 1999. (Belga photo - 13Kb)

The Charter considers the operational capacities of the OSCE from four different angles: field operations, peacekeeping operations, police operations and the Rapid Expert Assistance and Cooperation Teams (REACT) concept.

Field operations are set up on a case-by-case basis and most generally as long-term missions. Together with the High Commissioner on National Minorities, these are the tools with which the OSCE has been carving out a niche for itself in the area of conflict management since the 1990s. The Charter offers the first comprehensive (and non-restrictive) list of the tasks assigned to field operations: expert advice and assistance in all OSCE fields of competence; specialised technical support for the primacy of law and democratic institutions and the maintenance and restoration of law and order, good offices and mediation in situations of conflict; monitoring the implementation of peace-settlements, the conduct of elections and compliance with OSCE commitments; and post-conflict rehabilitation.

Pan-European peacekeeping emerged as a controversial subject within the OSCE during the early 1990s and still is. The United States argued that while the OSCE is not equipped for military peacekeeping, it has a useful political role to play in support of operations undertaken by other organisations (i.e. NATO). Russia, on the other hand, contended that existing texts provide an appropriate basis to allow the OSCE to conduct peacekeeping operations provided that they are supported by a prior United Nations resolution. Taking the middle ground, the European Union maintained that this question should not be approached from an either/or perspective.

Paragraph 46 keeps all options open. It confirms that the OSCE can, on a case-by-case basis and by consensus, decide to play a role, in peacekeeping, including a leading role, when participating States judge it to be the most effective and appropriate organisation. At the same time, it states that the OSCE could decide to provide the mandate covering peacekeeping by others and seek the support of participating States as well as other organisations to provide resources and expertise, and that it could serve as a coordinating framework for such efforts. But a closer look at some of the Charters other provisions those dealing with police operations and the REACT concept shows that actually it is the US position that has been endorsed, aimed at safeguarding NATOs new role and primacy in military peacekeeping in Europe.

Concerning police operations, paragraph 44 without reservation commits governments to strengthening the OSCEs role in civilian police-related activities as an integral part of the Organisations efforts in conflict prevention, crisis management and post-conflict rehabilitation. Limiting the OSCE to this type of function which includes activities such as providing training services, reforming paramilitary forces, preventing police from carrying out discriminatory measures, etc. clearly corresponds to the US view on the ideal division of labour: reserving a military role for NATO and a civilian role for the OSCE.

The then Russian president, Boris Yeltsin (left), meets his US counterpart, Bill Clinton, during the OSCE summit in Istanbul, Turkey. (Belga photo - 14Kb).

The REACT concept, which was forged by the United States and adopted by the OSCE, offers additional confirmation of this. The concept commits governments to develop at the national level, as well as at the OSCE level, the capacity to set up teams with a wide range of civilian expertise that the OSCE would be able to deploy to assist in conflict preven-tion, crisis management and post-conflict rehabilitation. Paragraph 42 states that the REACT concept has been developed to enable the OSCE to address problems before they become crises and rapidly to deploy the civilian component of a peacekeeping operation or large-scale or specialised operations, when needed.

REACT is due to become oper-ational by the end of June 2000 and will tend to specialise the OSCE in operations of an essen-tially civilian nature. To accommodate the planning and deployment of expanded OSCE field operations, including those involving REACT resources, paragraph 43 provides for an Operation Centre to be set up within the OSCE Conflict Prevention Centre.

An inter-institutional armistice

The EU-inspired Platform for Cooperative Security that is appended to the Charter is based on the premise that no single state or international institution has the capacity to respond in splendid isolation to the risks and challenges of the post-Cold War environment. It offers a kind of partnership contract to mutually reinforcing security-related institutions based on mutual comparative advantages, complementarity, pragmatic synergy, transparency and non-hierarchical relationships. The contract is open to those institutions whose members (both individually and collectively) cooperate among themselves freely and in full transparency; adhere to OSCE principles and commitments, as well as to its concept of a common security space free of dividing lines; and honour their arms control, disarmament and CSBMs engagements.

Different forms of cooperation between institutions could include liaison officers or points of contact, cross-representation at appropriate meetings, regular information exchanges, joint needs assessment missions, reciprocal secondment of experts, development of common projects and field operations, joint training efforts, etc. For the purpose of responding to specific crises, the OSCE also offers to serve as a flexible framework for cooperation.

The ultimate goal of the Platform is to develop a culture of institutional cooperation with a view to avoiding the duplication of efforts and the waste of resources. The Platform tasks the OSCE Secretary General to prepare an annual report on the interaction between international institutions in the OSCE area.

In a certain sense, the mere existence of the Platform is more significant than its contents. Given the unbridled competition that has come to characterise the activities of security-related institutions since the collapse of Communism, particular-ly during the early phase of the conflict in the former Yugoslavia, the Platform offers a kind of inter-institutional armistice. None of its provisions is contrary to NATO interests or practices. To a large extent, it represents a codification of the fruitful cooperation, which was developed between NATO and the OSCE to ensure joint monitoring of the situation in Kosovo, following the October 1998 meeting between US Special Envoy Richard Holbrooke and Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic.

Low-profile but expanding

A Yugoslav soldier patrols the streets of Bukos, 60 km north of Pristina, observed by an OSCE cease-fire monitor from his jeep 23 February 1999. (Belga photo - 11Kb)

For the OSCE, 1999 was not only the year of the signing of the European Security Charter. The 1994 Vienna was successfully updated after three years of intense negotiation. The 1990 Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe was adapted to reflect the changes brought about by the end of the Cold Document on Confidence- and Security-building Measures War, and signed by 30 OSCE participating states in spite of the tensions between Russia and the West over first Kosovo and then Chechnya. An OSCE mission of 700 international staff and over 1,000 local employees has been set up in Kosovo and is working closely with NATO, and special responsibilities have been taken on in the framework of the Stability Pact for South Eastern Europe.

In spite of the OSCEs inability to put an end to the conflict in Chechnya where Russia is openly disregarding some of the obligations that were subscribed to at Istanbul these pos-itive developments bear witness to the expanding operational role of this low-profile organisation.